And, of course, my favorite character is Hiro, the cute little time-traveling Japanese dude. The other day, R.A. had a very good point about Hiro and his companion, Ando: She said that all of the new "bro-mances" that are hitting the theatres these days ought to take a look at the relationship between these two characters (at least during the first season) and study what it is that makes an audience actually care about one another.

We're a little late to submit our essays for Heroes and Philosophy (Blackwell is publishing it this August.) But there are a lot of topics in this show, especially around the story of Hiro and his Quixotic quest. (The Driving Force of Narrative, Can Faith Ever Be Rewarded?, it looks like there'll be a chapter in Blackwell's book on Hiro, Nietzsche, and the Eternal Return of the Same,* etc.) So it is in this spirit that I want to talk about Hiro and time travel, and what the show's presentation of time travel tells us about our culture.

A little background: The basic premise of Heroes is that a select few humans scattered across the global have "evolved" different superpowers, and some of them are using these powers for good, others for evil, and others somewhere in between. (This is the same MacGuffin that is used in the X-Men films.) These powers vary from flight to super strength to mind reading, etc. Hiro Nakamura, of Tokyo, has the power to "bend space and time," meaning that he can teleport, slow time down or freeze it entirely, and travel both backwards and forwards in time.

Obviously, Hiro is not the first (nor the most famous) time-traveling super-hero. There's H.G. Wells' "The Time Machine" (1895) in which Wells coins the term "time machine," and of which the 1960 film adaptation gave me crazy Morlock-related nightmares as a kid. There's also Mark Twain's "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court" (1889), which of course was immortalized in the 2001 film adaptation, Black Knight.

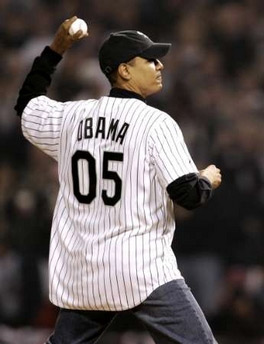

Pictured: Culture

More recently, we've had the Back to the Future trilogy and the Terminator films and TV show. So the point is that time travel has, for at least one hundred years, been an accepted part of popular culture. And that doesn't even take into account the ancient traditions of prophecy, revelation, and the Oracle. (Which also have an interesting role to play in Heroes.)

So we shouldn't be surprised when we encounter yet another time-traveler on television, or at the movies, or in books.** But what boggles my mind is the ease and readiness with which an audience, myself included, is able to suspend disbelief and accept that yes, this character or characters can travel backwards and/or forwards in time, whether it's through the use of a machine, magic, mutant powers, or whatever. It's part of the storyline and, for that sake, I'm willing to go along with the artist(s) on this one.

Now, there's one issue here about the physical possibilities of time travel. I'm no physicist, but everything that I've been taught says that time-travel, in the way that it is depicted "at the movies," is impossible. Now, the theory of relativity says that the faster I move, the slower that time moves in relation to where I am in space. So, in the sense, if I could get going really, really fast, (i.e., approaching the speed of light), I could slow time down for me, and then, when I return to normal speed, I would have "traveled" forward in time relative to all of you schmucks back on Earth. There are technological limitations to this kind of time travel, and so the debate about whether or not it is "possible," I think, remains open. But this isn't the kind of time travel that's in the movies. Writers are not obliged to give the scientific explanations behind their plot devices. It's magic. It's a worm-hole. Skynet invented/ discovered a new technology. Fine. That's the writer's prerogative, and I have no problem with that. My problem is more with the grammar of time-travel, fictional or non-fictional, how we understand (or think we understand) it, and how we talk about it.

Let's say, for a moment, that you meet me on the street later today, and ask me what I've been up to. I say, "I traveled back in time and prevented the nuclear destruction of Manhattan." Now, you can call me a liar.*** But you can't say that you don't understand me. I'm not speaking in tongues, I'm not simply stringing together a series of words in English ("Cat how is up.") I'm not inventing new or unusual uses for words ("Green ideas sleep furiously.") I'm reporting what I did, or believe that I did, today, and you can understand (or think you understand) me perfectly well.

I find this all fascinating because I think that the fact that most people are so willing and able to believe in this fantastic vision of time travel because it reflects, maybe even validates, how we see ourselves as active agents participating in our world. We decide, we choose, we regret, we make mistakes. All of these kinds of actions - so essential to our everyday lives - appear to carry with them the implication that the world could also be other than the way it is. And if we only had some way to "get back"**** there, whether it be a DeLorean, a genetic mutation, or the Holy Spirit, we could set things right. Of course, to actually do so is impossible, not in the sense that a man being able to fly or a woman having super-strength is impossible, but impossible in the sense that a gallon jug holding five quarts of milk is impossible.

As you can probably bet, this notion - that the world could be different than it is, has caused a whole host of problems in the silly history of Western Philosophy. It caused Leibniz to declare that this world is the best of all possible worlds, because God is a loving God, which in turn caused Voltaire to write Candide. More recently, this funny disposition of ours has led 20th Century philosophers to distinguish between names and descriptions, and to claim that some traits are essential and others contingent.*****

In On Certainty, Wittgenstein, while talking about whether or not we can ever truly know if 12 x 12 does indeed equal 144, he says, as almost a kind of aside: "Forget this transcendent certainty, which is connected with your concept of spirit." I'm taking this saying totally out of context, but this is how I feel about our willingness to suspend in disbelief in time travel. This idea of having the ability to right past wrongs - or to avert future disaster - is an extension and justification of our cultural beliefs that there is a concrete and knowable right and wrong, that I can over-come my past mistakes, that I never have to own or claim authorship of these mistakes, that I can erase or write over those things that I regret the most, that there is always and always will be a means for salvation.

Which leads us right back to the Eternal Return of the Same.

So we shouldn't be surprised when we encounter yet another time-traveler on television, or at the movies, or in books.** But what boggles my mind is the ease and readiness with which an audience, myself included, is able to suspend disbelief and accept that yes, this character or characters can travel backwards and/or forwards in time, whether it's through the use of a machine, magic, mutant powers, or whatever. It's part of the storyline and, for that sake, I'm willing to go along with the artist(s) on this one.

Now, there's one issue here about the physical possibilities of time travel. I'm no physicist, but everything that I've been taught says that time-travel, in the way that it is depicted "at the movies," is impossible. Now, the theory of relativity says that the faster I move, the slower that time moves in relation to where I am in space. So, in the sense, if I could get going really, really fast, (i.e., approaching the speed of light), I could slow time down for me, and then, when I return to normal speed, I would have "traveled" forward in time relative to all of you schmucks back on Earth. There are technological limitations to this kind of time travel, and so the debate about whether or not it is "possible," I think, remains open. But this isn't the kind of time travel that's in the movies. Writers are not obliged to give the scientific explanations behind their plot devices. It's magic. It's a worm-hole. Skynet invented/ discovered a new technology. Fine. That's the writer's prerogative, and I have no problem with that. My problem is more with the grammar of time-travel, fictional or non-fictional, how we understand (or think we understand) it, and how we talk about it.

Let's say, for a moment, that you meet me on the street later today, and ask me what I've been up to. I say, "I traveled back in time and prevented the nuclear destruction of Manhattan." Now, you can call me a liar.*** But you can't say that you don't understand me. I'm not speaking in tongues, I'm not simply stringing together a series of words in English ("Cat how is up.") I'm not inventing new or unusual uses for words ("Green ideas sleep furiously.") I'm reporting what I did, or believe that I did, today, and you can understand (or think you understand) me perfectly well.

I find this all fascinating because I think that the fact that most people are so willing and able to believe in this fantastic vision of time travel because it reflects, maybe even validates, how we see ourselves as active agents participating in our world. We decide, we choose, we regret, we make mistakes. All of these kinds of actions - so essential to our everyday lives - appear to carry with them the implication that the world could also be other than the way it is. And if we only had some way to "get back"**** there, whether it be a DeLorean, a genetic mutation, or the Holy Spirit, we could set things right. Of course, to actually do so is impossible, not in the sense that a man being able to fly or a woman having super-strength is impossible, but impossible in the sense that a gallon jug holding five quarts of milk is impossible.

As you can probably bet, this notion - that the world could be different than it is, has caused a whole host of problems in the silly history of Western Philosophy. It caused Leibniz to declare that this world is the best of all possible worlds, because God is a loving God, which in turn caused Voltaire to write Candide. More recently, this funny disposition of ours has led 20th Century philosophers to distinguish between names and descriptions, and to claim that some traits are essential and others contingent.*****

In On Certainty, Wittgenstein, while talking about whether or not we can ever truly know if 12 x 12 does indeed equal 144, he says, as almost a kind of aside: "Forget this transcendent certainty, which is connected with your concept of spirit." I'm taking this saying totally out of context, but this is how I feel about our willingness to suspend in disbelief in time travel. This idea of having the ability to right past wrongs - or to avert future disaster - is an extension and justification of our cultural beliefs that there is a concrete and knowable right and wrong, that I can over-come my past mistakes, that I never have to own or claim authorship of these mistakes, that I can erase or write over those things that I regret the most, that there is always and always will be a means for salvation.

Which leads us right back to the Eternal Return of the Same.

*Which is precisely the frustrating point of the PCP books. I mean, yes, there is an interesting connection between Heroes and the Eternal Return of the Same, but, on the other hand, Nietzsche's "theory" is one of the most maddening, complicated, and mysterious ideas in the history of Western Philosophy, one that many brilliant scholars have spent entire careers studying (Heidegger, Foucault, etc.), and here you have a 15-page essay "dealing" with it, written by a T.A. at Berkeley. You can see how this might rub some people the wrong way. Of course, I think that anyone who actually believes this is missing the raison d'etre for these books in the first place.

**Personally, I still have a fond place in my heart for The Time Traveler's Wife, even if it is severely lacking in murderous cyborgs and nuclear holocausts.

***Although, interestingly, you wouldn't have a means to prove to me that I was lying.

****Writing this just reminded me of Aymara, the language of a South American indigenous tribe. To the Aymara, the past is in front of us, and the future behind, because we have knowledge (we can see) the past, but the future is unknown. Here's the posting of the Science Now magazine article that I put up on my old blog three years ago.

*****If you're not into long philosophy quotes, skip this note.

The following is from Saul Kripke's incredibly influential essay, "Naming and Necessity," (1972) which illustrates both the awesomeness and ridiculousness of analytic philosophy:

Let's call something a 'rigid designator' if in every possible world it designates the same object, a 'nonrigid' or 'accidental designator' if that is not the case. Of course we don't require that the objects exist in all possible worlds. Certainly Nixon might not have existed if his parents had not gotten married, in the normal course of things. When we think of a property as essential to an object we usually mean that it is true of that object in any case where it would have existed. A rigid designator of a necessary existent can be called 'strongly rigid.'There may be an infinite number of possible worlds, but there's only one Nixon.

One of the intuitive theses I will maintain in these talks is that names are rigid designators. Certainly they seem to satisfy the intuitive test mentioned above: although someone other than the U.S. President in 1970 might have been the U.S. President in 1970 (e.g. Humphrey might have), no other than Nixon might have been Nixon. In the same way, a designator rigidly designates a certain object if it designates that object wherever the object exists; if, in addition, the object is a necessary existent, the designator can be called 'strongly rigid.' For example, "the President of the U.S. in 1970" designates a certain man, Nixon; but someone else (e.g., Humphrey) might have been the President in 1970, and Nixon might not have; so this designator is not rigid.